“For half a century, ACA has been providing the world … with advocacy, analysis, and awareness on some of the most critical topics of international peace and security, including on how to achieve our common, shared goal of a world free of nuclear weapons.”

The Overlooked Importance of the Korean Military Agreement

April 2025

By Daeyeon Lee

Top leaders from North Korea and South Korea met in Pyongyang Sept. 19, 2018, to reduce tensions and build confidence on the Korean peninsula through the landmark Comprehensive Military Agreement (CMA). South Korean President Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un signed first, followed by their defense ministers. This deliberate sequence was proposed by South Korea to intentionally demonstrate the leaders’ commitment to the CMA, according to Choi Jong-kun, who was then South Korean secretary for peace and arms control.1

Previously, the two Koreas had signed 12 military agreements, none of which were ever implemented.2 In contrast, the CMA was put swiftly into action by both sides to manage security risks and build confidence across all border areas. Despite the collapse of the 2019 North Korean-U.S. summit in Hanoi, border stability largely persisted, although the diplomatic deadlock stalled further implementation of key CMA provisions.

Over time, the agreement deteriorated and was ultimately abandoned amid rising tensions over North Korea’s provocations and South Korea’s conservative shift. Its contributions to regional security were overshadowed as the focus turned toward South Korea’s nuclear ambitions, U.S. extended deterrence, and North Korea’s deepening military ties to Russia. Highly susceptible to shifts in U.S.-North Korea relations and South Korean domestic politics, the CMA’s trajectory was short-lived. Nevertheless, while in effect, it served as a significant arms control measure, alleviating tensions and fostering confidence between the two Koreas.

Origins of the CMA

In mid-2017, Moon took office, providing a measure of stability after President Park Geun-hye’s impeachment. However, nuclear tensions escalated as North Korea and the United States engaged in a war of words. In response to North Korea’s provocations, U.S. President Donald Trump warned of “fire and fury,” prompting Kim to threaten to strike Guam.3 When Pyongyang conducted its sixth nuclear test in September 2017, Trump vowed to completely destroy Pyongyang, leading North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Yong Ho to declare Trump’s statement a declaration of war.

As fears of nuclear conflict grew, Moon sought to de-escalate tensions, condemning North Korea’s provocations while vowing, “[t]here will not be a war again on the Korean peninsula.”4 Tensions escalated when Pyongyang tested a Hwasong-15 intercontinental ballistic missile November 29, 2017, declaring its “the state nuclear force” complete.5 Rather than taking countermeasures, Moon proposed suspending South Korea-U.S. military exercises during the 2018 Winter Olympics, a move the United States accepted. In response, North Korea halted provocations, participating in the Olympics and engaging in dialogue with Moon and Trump, briefly stabilizing the region.

Within three months of the CMA’s signing in September 2018, both sides demolished 22 guard posts in the Demilitarized Zone, disarmed the Joint Security Area, and ceased hostile acts across all border areas at sea, on land, and in the air.6 They halted artillery fire, and battalion-level field maneuvers, prohibited unannounced flights in the designated no-fly zone, and covered the barrels of naval and coastal guns and sealed them.

Although Kim’s diplomatic shift in 2018 helped facilitate the CMA’s implementation, the agreement itself played a critical role in avoiding escalation even when diplomacy stalled. According to South Korea’s 2022 defense white paper, Pyongyang violated the CMA twice between 2018 and 2022, with no significant rise in tensions.7 Beyond the de-escalation, the CMA improved South Korean security by significantly reducing North Korean infiltrations and local provocations, which previously had averaged more than 20 incidents per year but dropped to just one between 2018 and mid-2022.

Although Kim’s diplomatic shift in 2018 helped facilitate the CMA’s implementation, the agreement itself played a critical role in avoiding escalation even when diplomacy stalled. According to South Korea’s 2022 defense white paper, Pyongyang violated the CMA twice between 2018 and 2022, with no significant rise in tensions.7 Beyond the de-escalation, the CMA improved South Korean security by significantly reducing North Korean infiltrations and local provocations, which previously had averaged more than 20 incidents per year but dropped to just one between 2018 and mid-2022.

The agreement also benefited civilians, particularly in the disputed Yellow Sea (West Sea) region, where past clashes in 1999 and 2002, the 2010 sinking of the Cheonan naval vessel, and the 2010 Yeonpyeong Island bombardment, had resulted in casualties and trauma.8 Following CMA implementation, the South Korean government expanded fishing hours for the first time since 1964 and extended fishing areas in 2019.9 By the CMA’s third anniversary, residents of the region experienced a period of peace and increased fish catches.

The Agreement Collapses

Progress toward further CMA implementation ceased after the 2019 Hanoi summit at which Kim and Trump failed to reach a nuclear deal. Kim offered to dismantle the Yongbyon nuclear facility and its nuclear weapons institute in exchange for partial UN sanctions relief, but Trump demanded the dismantlement of four additional nuclear facilities and full disclosure of North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction programs.10 When talks deadlocked, North Korea ignored Moon’s request to continue implementing CMA provisions, including further guard post demolitions, remaining excavations of war remains, and the formation of an Inter-Korean Military Committee.

The COVID-19 pandemic further deepened the impasse as North Korea closed its border in 2020. In mid-2022, South Korea’s conservative shift under President Yoon Suk Yeol hardened the country’s stance toward North Korea, which included advocating for a “preemptive strike” and “peace through strength.”11 During a visit to the DMZ in September 2023, Yoon ordered South Korean forces to retaliate against North Korea without hesitation if provoked.

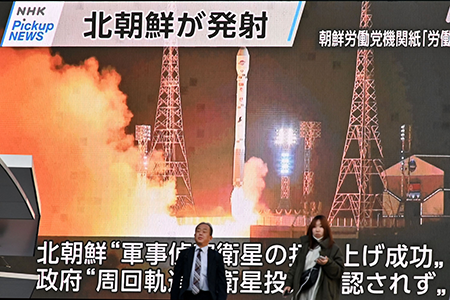

On November 21, 2023, North Korea successfully launched a spy satellite after a few failures. The following day, Yoon suspended the CMA-established no-fly zone restrictions, which prohibit fixed-wing aircraft over the military demarcation line.12 Although the satellite launch violated UN sanctions, it had nothing to do with the CMA. The next day, North Korea announced that it would withdraw completely from the agreement.

Since then, tensions have escalated due to North Korea jamming South Korean GPS signals and its frequent artillery drills.13 South Korea has responded by expanding combined, joint military exercises with the United States and Japan. Finally, June 3, 2024, Yoon suspended the CMA after a series of North Korea-launched trash balloons that caused damage in South Korean cities.

Critics argue that the CMA was ineffective to begin with, weakening South Korean surveillance capabilities through the no-fly zone and allowing 3,600 cross-border violations.14 But the Moon administration has countered that, saying North Korea lacked medium-altitude and high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft and spy satellites, while the South, with U.S. support, maintains full surveillance over North Korean territory.15

Moreover, a South Korean civic group, People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy, filed an information disclosure request with the South Korean Defense Ministry to confirm the number of total CMA violations by North Korea. The ministry confirmed 17 such violations, including ground hostile action, artillery fire, and missile launches within the maritime buffer zone, and an airspace violation in the no-fly zone, along with 3,400 instances in which North Korea opened coastal artillery ports between November 2018 and October 2023.16 Significantly, these openings had not been counted as violations by the Moon administration, which considered them “facility management,” rather than serving an offensive purpose.17

Today, concerns over the likelihood of nuclear war on the Korean peninsula as a result of inadvertent conflicts between the two Koreas are growing again. In 2022, North Korea updated its nuclear doctrine, legalizing preemptive nuclear strikes to protect its leadership and nuclear command-and-control operations. In January 2024, Kim announced that North Korea is no longer seeking reunification because South Korea is the North’s primary adversary. Under these circumstances, if North Korea makes any misjudgment or miscalculation about South Korean military activities, it is more likely to use nuclear weapons to compensate for its relatively weak conventional forces. The risks of nuclear war are heightened in the absence of tension-reduction measures, such as the CMA.

Reactivation of the CMA

Trump’s return to the White House in January has added a new factor to geopolitics. He has expressed a willingness to engage China and Russia on nuclear arms control.18 His secretary of state, Marco Rubio, has emphasized the importance of reducing risks on the Korean peninsula to prevent inadvertent war. The administration also is seeking to revive direct engagement with Kim.19

As one step in achieving these objectives, the Trump administration should encourage Seoul to reactivate the CMA as a means of restarting and sustaining dialogue with Pyongyang. Although the North-South relationship is hostile, a progressive South Korean candidate, who condemned Yoon's suspension of the CMA last June and is pursuing reconciliation with Pyongyang, has a strong chance to succeed Yoon, once a court ruling on Yoon’s impeachment is decided in April.20

Under current circumstances, any inadvertent conflict on the Korean peninsula could lead to a confrontation, with the South Korean-U.S. alliance facing off against North Korea, backed by China and Russia. Even if North Korean-U.S. nuclear talks resume, North Korea’s threat perception of South Korea would remain. As a confidence-building and risk-reduction measure, the CMA has demonstrated that it can help manage risks on the Korean peninsula.

ENDNOTES

1. Jong-kun Choi, The Power of Peace, (Seoul: Medici Media, June 20, 2023), p. 103.

2. Ibid., KFN TV “2021 Defense Focus: The 3rd Anniversary of the September 19 Military Agreement, Its Significance and Achievements” YouTube, September 17, 2021.

3. Meghan Keneally, “From ‘Fire and Fury’ to ‘Rocket Man,’ the Various Barbs Traded Between Trump and Kim Jong Un,” ABC News, June 11, 2018, accessed September 1, 2024; “North Korea Calls Trump Tweet ‘a Declaration of War,’” CBS News, September 25, 2017, accessed September 1, 2024.

4. Alex Ward, “The President of South Korea Has a Strong Message for Trump,” Vox, August 17, 2017, accessed September 1, 2024.

5. Reuters, “North Korea Says New Missile Puts All of US in Striking Range,” BBC News, November 29, 2017, accessed September 19, 2024; Moon Jae-in, From the Periphery to the Center: Moon Jae In Memoirs of Foreign Affairs and Security, (Seoul: Gimmyoung, May 18, 2024), pp. 139-141.

6. Choi, The Power of Peace, pp. 111-114; Korea Policy Briefing, “September 19 Military Agreement,” accessed August 8, 2024.

7. South Korea Ministry of National Defense, “Defense White Paper 2020,” p. 393, accessed September 9, 2024, “Defense White Paper 2022,” p. 353, accessed September 9, 2024.

8. Andrew Yeo, “Inter-Korean Relations,” The National Committee on North Korea, September 2023, accessed September 19, 2024; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “The Yŏnp’yŏng-do Incident, November 23, 2010,” 38 North, January 11, 2011, accessed September 1, 2024.

9. KBS News, “West Sea Five Islands: Fishing Grounds Expanded by 84 Times Yeouido’s Size, Night Fishing Revived After 55 Years,” February 20, 2019, accessed September 19, 2024; KFN TV, “2021 Defense Focus: The 3rd Anniversary of the September 19 Military Agreement, Its Significance and Achievements,” YouTube, September 17, 2021.

10. Seigfried S. Hecker, Hinge Points: An Inside Look at North Korea’s Nuclear Program (Stanford University Press: January 10, 2023), pp. 338-340; Moon Jae-in, From the Periphery to the Center, p. 323.

11. Kim Mi-na and Kwon Hyuk-chul, “Yoon Says Preemptive Strike Is Only Answer to N. Korea’s Hypersonic Missiles,” Hankyoreh, January 12, 2022, accessed September 1, 2024; An Yong-su, “President Yoon Says, ‘If North Korea Provokes, Respond Without Waiting Even a Second’ [Comprehensive Report],” Yonhap News Agency, October 1, 2023, accessed September 1, 2024.

12. The National Committee on North Korea, “Agreement on the Implementation of the Historic Panmunjom Declaration in the Military Domain, signed by the Republic of Korea and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, September 19, 2018,” accessed September 1, 2024,; Soo-Hyang Choi, “North Korea Scraps Military Deal with South, Vows to Deploy New Weapons at Border,” Reuters, November 23, 2023, accessed September 1, 2024.

13. Won Hyung-min, “[Graphic] Recent North Korean Provocations and Suspension of the September 19 Military Agreement,” Yonhap News Agency, June 4, 2020, accessed September 1, 2024.

14. Frank Aum, “North Korea’s Satellite Launch Adds a Spark to Already Simmering Tensions,” United States Institute of Peace, November 27, 2023, accessed September 1, 2024; “Shin Won-sik: ‘North Korea Violated the 9/19 Agreement 3,600 Times…’ Suppressing Ambitions with ‘Powerful Force,’” Dong-A Ilbo, December 21, 2023, accessed September 1, 2024.

15. MBCNEWS, “‘Jukgangkkeut’ and ‘Great Change’ - The Chicken Game Between North and South Korean Hardliners), YouTube, January 7, 2024.

16. People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy, “[Statement] Withdraw the Suspension of the September 19 Military Agreement,” November 22, 2023, accessed September 1, 2024.

17. Kwon Hyuk-chul, “Five Years After the Buffer Zone Was Nullified… A Ticking Time Bomb in a South-North ‘Surveillance Contest’), Hankyoreh, accessed September 1, 2024; Josh Smith, “New North Korea Law Outlines Nuclear Arms Use, Including Preemptive Strikes,” Reuters, September 9, 2022, accessed September 1, 2024.

18. Arms Control Association, “ACA Welcomes Trump’s Acknowledgement of the ‘Tremendous’ Cost and Dangers of Nuclear Weapons and Interest in ‘Denuclearization’ with Russia and China,” January 24, 2025, accessed September 19, 2024; “Rubio Says He’ll Explore Ways to Lower Risks of ‘Inadvertent’ Inter-Korean War,” The Korea Times, January 16, 2025, accessed February 20, 2024.

19. Trevor Hunnicutt, “Exclusive: Trump Team Weighs Direct Talks with North Korea’s Kim in New Diplomatic Push, Sources Say,” Reuters, November 26, 2024, accessed February 20, 2024.

20. “Who Is Lee Jae-myung, South Korea’s Possible Next President?” The Economist, January 30, 2025, accessed January 30, 2024; Young-ho Kim, “Lee Jae-myung on the Suspension of the September 19 Military Agreement: ‘For Two Years, the Government Has Taken Out Its Anger on the North with Verbal Bombs’,” Kyeonggi Ilbo, June 5, 2024, accessed February 20, 2024; Da-sol Kim, “Yoon Suk Yeol’s Impeachment Verdict Could Be Pushed to April,” The Korea Herald, March 26, 2025, accessed March 26, 2024.